Integrating flow sensor technology into an existing system is rarely a plug-and-play exercise. Most engineering challenges arise not from the sensor itself, but rather how it interfaces with the process, the control architecture and the long-term operating environment. A disciplined, engineering-led approach, supported by early specialist involvement, can significantly reduce cost, commissioning time and operational risk.

1. Define the measurement requirement first

Successful integration starts by understanding why the measurement is required. Is the goal real-time monitoring, totalising for reporting or billing, or closed-loop process control? Is the requirement permanent, or only needed for commissioning, diagnostics or short-term verification? Avoid over-specification that adds unnecessary complexity and cost.

In many cases, engineers default to complex solutions when simpler approaches would suffice. For example, finding a flow switch to fit system dimensions can be problematic and expensive, whereas a low-cost flow sensor feeding the customer’s existing processor can perform the same function reliably. Similarly, applications linked to dispensing or batching may be better served by volume-based measurement with simple on/off control, rather than continuous closed-loop flow control.

Where measurement is temporary, clamp-on ultrasonic meters or even timed collection methods can provide sufficient data without permanently modifying an established system.

2. Involve sensor specialists early

One of the most common integration failures occurs when sensors are treated as an afterthought. Systems are often fully designed – complete with IoT connectivity, AI machine learning and visual polish – only for it to become clear that there is no physical space, straight pipe length or access to install the required sensor.

Bringing sensor specialists into the design process early avoids costly redesigns and compromises. Even in long-established systems, understanding sensor constraints early clarifies what can realistically be integrated and how. Early engagement also helps answer key questions: can one sensor serve multiple systems, or does each loop require its own device?

“When system design engineers talk openly about the requirements as they see them, the supplier can assist with advice on the best available technology and the limitations of that technology, from a measurement, maintenance and integration level,” says Neil Hannay, Titan’s Senior Development Engineer.

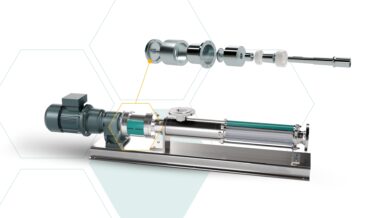

“Titan is able to provide CAD models to allow engineers to draw up the installation correctly,” adds Neil, also noting the following key support areas expected from a flow sensor supplier:

- Is the supplier able to assist with clear installation and connection instructions for your system?

- Will the sensor arrive preconfigured and wired to your requirements?

- What form of on-going support can the supplier provide?

- Assess lifecycle cost, not just purchase price

3. Assess lifecycle cost, not just purchase price

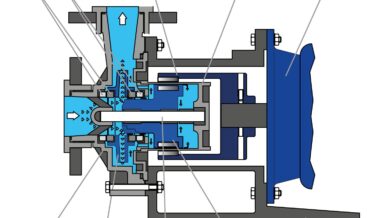

From an engineering standpoint, initial purchase price is a poor indicator of true cost. Low-cost mechanical meters may appear attractive, but wear, contamination sensitivity and frequent recalibration can introduce disproportionate operational risk in established processes.

Non-intrusive technologies – such as ultrasonic flowmeters – eliminate moving parts, pressure loss and routine recalibration. Although the upfront cost may be higher, reduced maintenance, downtime and intervention often result in a lower total cost of ownership. Meter selection should therefore reflect service life, accessibility and process criticality, not just capital cost.

4. Design for real operating conditions

Flowmeters are often specified for nominal operating conditions, yet many integration problems arise during start-up, shutdown or cleaning cycles. Engineers must consider flow range, pressure and temperature alongside transient conditions such as pulsation, entrained air, temperature excursions and cleaning-in-place procedures.

Equally important is compatibility with existing PLCs, SCADA systems and legacy instrumentation, which may have limited signal conditioning or communication flexibility.

5. Verify material compatibility and system tolerance

Physical and chemical compatibility is a common root cause of premature system failure. All wetted components – seals, bearings, magnets and internal materials – must be suitable for the process fluid and operating conditions over the full operating life.

Beyond the sensor itself, the wider system must be considered. Hydraulic shock, over-range events, temperature variation and future process changes can all compromise performance and life expectancy. Engineering appropriate margins at the sensor stage is often far simpler than modifying pipework, controls or software later and much cheaper than managing process failures.

6. Choose technology pragmatically and read installation instructions!

No single flow technology suits every application. Coriolis meters offer exceptional accuracy but may be hard to justify in low-flow or cost-sensitive systems. Electromagnetic meters depend on fluid conductivity, thermal meters can respond slowly, while ultrasonic meters often provide a balanced mix of performance, ease of integration and long-term stability.

Regardless of technology, correct installation remains critical. Adequate straight lengths, thorough system flushing, controlled commissioning and sound electrical practice eliminate many apparent “sensor faults” before they occur.

Ultimately, reliable flow measurement is achieved not through smart communications or advanced analytics alone, but through a correctly specified, well-integrated sensor. An engineering-led approach, supported by experienced suppliers, clear installation guidance and realistic lifecycle planning, remains the most effective way to minimise integration challenges in existing process systems.

More information can be found at www.flowmeters.co.uk